OK, a 56-year-old person walks into a health clinic for further evaluation of their persistent low back pain. They reported being in a motor vehicle collision where a vehicle turned in front of theirs and despite their best attempts at braking, a frontal collision mechanism resulted. They did all the right things. They went to their doctor who encouraged them to keep moving, advised them to purchase some over-the-counter medications and referred them to physiotherapy. They subsequently attended physiotherapy and were diligent with attendance and performance of home exercises. Over the ensuing months, the central low back pain started to spread a little towards their buttocks – some morning stiffness was evident and functional deficits were becoming more prevalent. They noticed difficulty with sitting for a prolonged period, or sustained cleaning or yard work. They kept going to physiotherapy and massage, which was noted to provide partial and temporary symptom relief. They were concerned regarding non-progress and as such requested an MRI. Now, with that MRI in hand, they walk into your office asking for treatment for their ‘degenerative disc disease’ and ‘facet joint degeneration’. They are as excited as the Pointer Sisters were back in 1982, as they have been clever enough to receive this diagnosis via MRI and a Dr. Google visit.

Image Credit: Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014“. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436

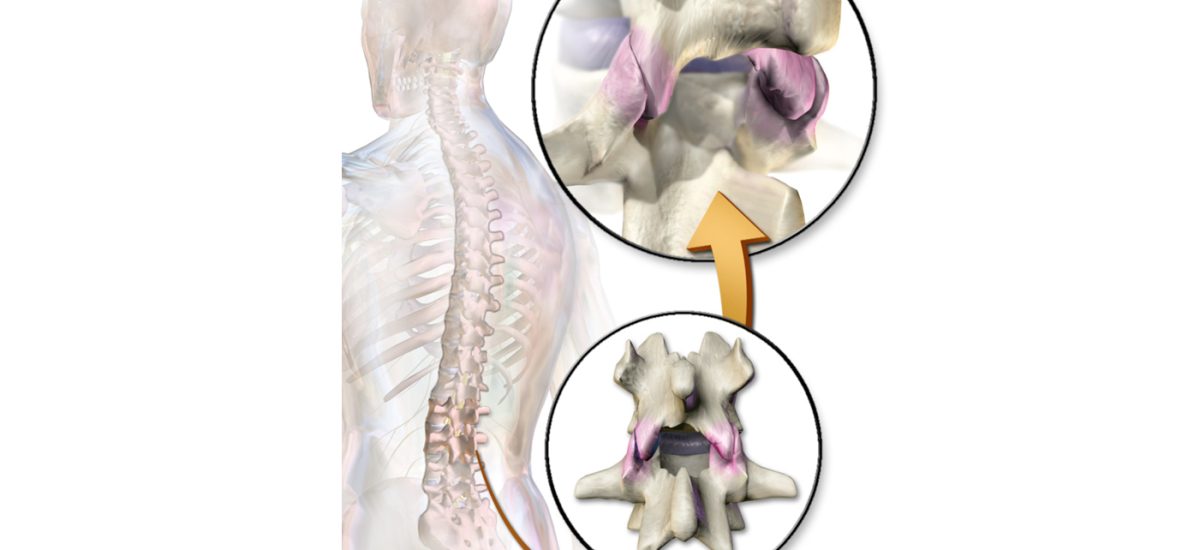

Common MRI Results in 50-60 year olds.

Systematic reviews (a summary of all literature on a particular topic) have demonstrated that there are many imaging findings in people with NO symptoms. And, as we age, these findings become more common. In a 50-year-old (as an example), 80% of people without low back pain demonstrate findings on MRI consistent with disc degeneration1. Disc protrusions are reported in 36%, annular fissures in 23% and facet degeneration in 32% of people without symptoms. Thus, there is a possibility that the MRI findings for a person with low back pain are coincidental and not relevant to their clinical presentation. Now, we might wish to extend a little word of caution right here. We commonly hear clinicians say to their patients – these findings are quite common and many people your age in the community have these findings without symptoms. That is not totally true. In the systematic review where these findings arose, a grand total of 311 people in 10 separate studies contributed to these findings (for disc degeneration, and only 53 people in 3 studies for the annular fissure and facet degeneration studies) – so, when we are talking about ‘populations’, that is not many people! And it gets less and less as we report the older age findings. For 60 years and older, only 80 people contributed to the findings for disc degeneration…But, it is possible obviously!

Now stats are stats, and the key to stats is determining what your relative risk is – are these findings any different in those with low back pain, and that’s where things get interesting. The same authors above looked at this in people younger than 50 years (they had enough data to do this comparison), being so clever and all. And maybe not surprisingly to all those with low back pain out there, most findings on MRI were more prevalent in those with low back pain, especially when it came to disc problems – disc degeneration, disc bulge and disc protrusion or extrusion2.

So, where does this leave us – well, another systematic review helps us here. A group of Aussies also looked at other tests apart from MRI to determine if certain anatomical structures in the low back were associated with pain3. Again, they showed that MRI findings of disc degeneration, annular fissures, Modic changes and even examination results (centralization phenomenon) were associated with a person’s symptoms. Interestingly, if the MRI did not demonstrate certain Modic findings or physical examination was negative, it was not possible to rule out the presence of symptoms. There was increased probability that a person with uptake of the facet joints on bone scans presented with symptoms, but the converse was not true. The same held true for a cluster of tests for the sacro-iliac test and an absence of midline low back pain.

Why Might This Be Helpful?

In certain cases, where appropriate conservative therapy consisting of multimodal rehabilitation – most particularly, graded exercise therapy, advice, education, re-assurance and possibly manual therapy has been provided and a person fails to improve, then medical interventions may be possible to improve a person’s quality of life related to their low back pain. In that case, seeking tests to inform a person of the anatomical origin of their symptoms may provide an opportunity to progress to these interventions. So, hopefully, knowing the above, allows the best tests to be ordered and appropriate findings to be determined. But this isn’t magic – even if you do find the source of person’s symptoms, the treatment options may very well be limited – discs, I’m thinking of you. In those instances, validation may have been helpful, and institution of a daily routine to manage symptoms can provide reassurance of an appropriate care package having been delivered.

References:

1. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36(4):811-6. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A4173.

2. Brinjikji W, Diehn F, Jarvik J, et al. MRI findings of disc degeneration are more prevalent in adults with low back pain than in asymptomatic controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2015;36(12):2394-2399.

3. Han CS, Hancock MJ, Sharma S, et al. Low back pain of disc, sacroiliac joint, or facet joint origin: a diagnostic accuracy systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2023;59:101960. DOI: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101960.